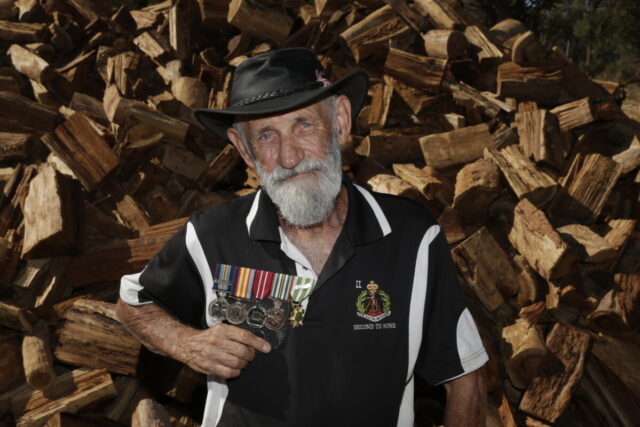

Vietnam veteran Norm Heslington has lived in Australia for 70 years, but has been denied from calling himself Australian.

“All my life I’ve struggled to show who I am,” he said.

“I can’t leave the country – my company went back to Vietnam for a reunion and I couldn’t go for fear of my permanent residency visa being cancelled on me.

“It really sticks in my craw. We should have been granted citizenship for fighting for this country.”

Norm was orphaned shortly after he was born in England, in 1950.

With post-war children’s homes bursting at the seams, many wards of the state were shipped out to the colonies for a better life.

So, four-year-old Norm became a student at Fairbridge Farm School in Pinjarra.

More than 1000 child migrants were sent from England to the farm school after World War I, and another 1520 children after World War II.

After a tumultuous start to life, Norm said he relished the fresh start he was given in his adopted country.

“We all left our baggage in our suitcase and got on with life,” he said.

“I spent more years there than any other kid, and I loved it. It was a wonderful place to grow up.”

And Norm wasn’t the only student who repaid the chances Australia gave him with loyalty.

“During World War II, 542 old Fairbridgians – half of those who went there – volunteered for service in the armed forces,” he said.

“They felt so strongly about the country that adopted them. And yet many of them died non-citizens.”

When Norm realised his AFL career was not going to take off, he signed up early for his national service.

“I thought, I’ve got nothing better to do so I’ll chuck my lot in. And then my ballot got called up,” he said.

He signed up for the infantry, and marched out of Townsville with the 2nd Battalion Royal Australian Regiment under Platoon Commander Phillip John McNamara, who later became Brigadier McNamara.

Norm said he has no regrets about Vietnam or being conscripted.

And he arrived back in Townsville to the heroes’ welcome that many down south never received.

For many years after he returned from Vietnam, Norm published a gardening magazine in Perth.

And then a friend showed him the art of hawking jewellery on Hay Street – the returns on which were too thrilling to be ignored.

“And I was good at it,” he said.

Unfortunately, it was illegal to pedal wares on the street without a licence in the City of Perth.

But Norm said when he applied for a licence, he was told that no such licence existed. He took his fight all the way to the Supreme Court.

“I was locked in mortal combat with the Perth City Council for 15 years,” he said.

“And I was jailed three times for selling without a licence.

“One time I wore a convict suit and held a ‘going to jail’ sale, then showed up to court wearing the same suit.

“I was ordered to go home and change by the judge, so I bought a three-piece tuxedo with tails and returned.”

Norm said it was only when he realised the court would be sending him to jail that he decided to take his family “on a little holiday to Bali before the ‘big holiday’”.

It was whilst applying for a passport that Norm discovered he wasn’t an Australian citizen by law.

“So, I applied for citizenship, and it was rejected on grounds that I had outstanding violations, being breaches of the City of Perth by-laws,” he said.

“They told me I’d failed the ‘character test’. Piss off. Failure to have a busking licence is hardly a reason for denying citizenship.”

He wrote to Prime Minister Bob Hawke – being a man of the people – and pointed out he probably deserved citizenship as a returned serviceman.

He received a pro forma response that the ministry had the right to ‘refuse citizenship if it so wishes’.

At the following ANZAC Day ceremony, Norm burnt his service medals in front of then-Premier Brian Burke.

“What’s the good in having those if my service means nothing?” he said.

“It even took the government 30 years to give me compensation for the illness I acquired during my service in Vietnam.

“Although I do have to say that since receiving my pension, the Department of Veterans Affairs has been wonderful.”

Norm – who lives in Wandi and has a wood business in Oakford – said he’s taken up his case for citizenship with every serving immigration minister since the 80s, and also former and current members for Canning, Don Randall and Andrew Hastie.

“But it always falls on deaf ears,” he said.

“I reckon to get a job in the immigration department you need to get a chest x-ray to see if you’ve got a heart – if you do, you’re out.”

He said he’s given up hope of winning this fight.

When The Examiner approached the federal government for a response, we were told by Minister for Veterans Affairs Matt Keogh that there are “already provisions in place for a person to apply for citizenship after they have completed 90 days of relevant Defence service”.

“These non-citizens are otherwise required to meet normal citizenship requirements, including meeting the character test for their application to be successful. It is not appropriate to comment on an individual case,” he said.

The minister for immigration had not supplied a response to our questions by the time of publishing.

But Norm said he refuses to apply for citizenship again.

“I guess we’re in a Mexican stand-off. But why should I have to apply for something I should have been granted freely,” he said.

“Alternately, they shouldn’t have been allowed to conscript non-citizens to fight for Australia.

“I have an issue with politicians of all colours being too lazy to draft a piece of legislation around this.

“It’s so easily corrected, it’s not going to cost a penny, and it’s the right thing to do.

“I’m 73 and I’d like to be buried as an Australian citizen.”