Huntingdale Kate Purcell, 41, describes herself as “a very fun, happy person” who enjoys music, fashion, catching up with friends, and spending time with her partner at the pub on a sunny day.

But for much of her life, her relationship with food has been complicated, built by years of struggle with an eating disorder that began when she was still in school.

How it started

She said as a child she enjoyed food, but looking back, she believes emotional eating played a part because she “wasn’t really happy”.

Her relationship with food changed in Year 8, when she was around 12 or 13, after teasing and rejection from a boy she liked.

“I started to restrict my diet,” she said.

By Year 10, at just 14 years old, she was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa.

According to Kate, those teenage years were isolating and frightening.

“I started off visiting Princess Margaret Hospital and being diagnosed, and then quite quickly, I was admitted to hospital for weight gain and re feeding,” she said.

“And then it just kind of got more severe over the next couple of years.”

She said one of the biggest misunderstandings about anorexia is the belief it is simply about food.

“It looks like it’s about food, but it’s actually not about food,” she said.

Years later, Kate was diagnosed with A-typical anorexia in her 30s, which she described as anorexia, but without being severely underweight.

“You’re still in a relatively healthy weight, but you still have that desire for weight loss and that fear of weight gain,” she added.

Now older, she said the illness did not take over her entire life the way it did when she was a teenager.

“I have a life now,” she said. “I have a job, I have a partner, I have friends, I have family, I have passions, I have hobbies, so it doesn’t take up as much space in my life as it used to.”

Kate said the difference now is that she knows who she is beyond the eating disorder.

“I have more of a grasp on knowing who I am,” she said. “I know who Kate is, aside from her eating disorder.”

When she was a teenager, she noted the eating disorder became her identity.

“I didn’t know who I was aside from my eating disorder,” she said.

In recent years, she began to recognise she could not keep going down the same path.

“I was starting to lose a fair bit of weight, and I was starting to restrict again,” she said.

But she also realised she was tired of pretending she was completely recovered.

“I don’t want to keep telling this lie that I’m this recovered person,” she said. “I still have some things to work out with this stuff.”

She said she is motivated to make the rest of her life “the best of my life”, and she does not want an eating disorder to be part of it.

What recovery looks like

Recovery for Kate is about shifting focus away from constant thoughts about food, weight, and appearance.

“Recovery, I suppose, is not thinking and thinking about food and weight as much as someone with an eating disorder,” she said.

She added that day-to-day recovery now looks like nourishing her body and trying to let go of guilt around eating.

“Just being at peace with enjoying food and not being so focused on a number on a scale,” she said.

She also explained about what she believes is one of the hardest parts of recovery, something she says people do not talk about enough.

“The hardest part of recovery from an eating disorder is putting on the weight that’s required,” she said.

Kate said that weight restoration can be distressing because the illness drives a constant fear of weight gain.

“You have an illness that basically dictates to you on a daily basis that you need to be thin,” she said.

“And then the hospital, the doctor, the dietitian, they’re telling you you need to put on weight.”

She said it can become a painful battle between what treatment requires and what the eating disorder demands.

“So, you start putting on weight, and that can be extremely distressing and extremely traumatising,” she said.

Kate said during that time, she had to rely on other people’s perspective when she could not see herself clearly.

“You have to really listen to those other people and trust the other people, because you can’t see things clearly,” she said.

“You’re enough”

When asked what she wished someone had told her when she was younger, she said “You’re enough.”

“You don’t need to be thin, you don’t need to be so focused on what you look like, because you as a person, are beautiful.”

She said an eating disorder takes away the parts of a person that make them feel alive.

“Everyone has a sparkle in their soul, and an eating disorder just dulls it.”

Why she wrote a book

Kate has worked in mental health for about 12 years and says she has a passion for helping others in a peer support role.

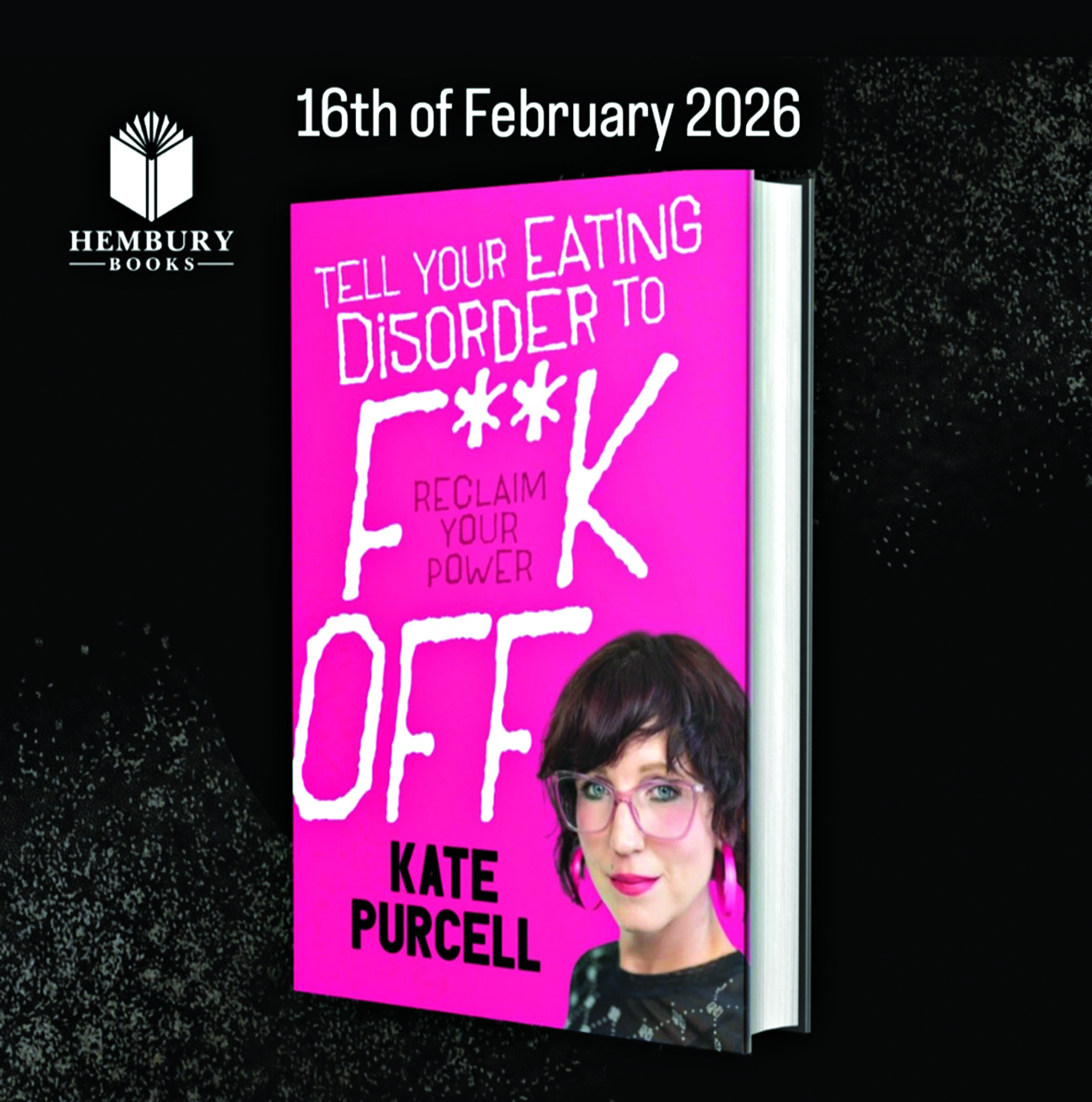

That desire to help, combined with her experience, is what led her to write her latest book, ‘Tell Your Eating Disorder to F**k Off.’

“I realised that I’ve got valuable knowledge and wisdom around eating disorders, and I wanted to share that with others,” she said.

“I know that what helps me will help other people in their journey to recovery.”

She described writing as cathartic and healing.

“I don’t think I find any part of writing the book particularly emotionally hard,” she said. “I find it quite healing.”

The book’s title is blunt and confronting, but Kate said it reflects the kind of mindset she believes people need when fighting an eating disorder.

“When you are battling an eating disorder, you have to be very strong and assertive with it,” she said.

“You really do have to get to a point where you’re like, I’m literally going to tell my eating disorder to f**k off,” she added.

A message for families

Kate believes WA needs more support for people experiencing eating disorders.

“I know there are some great services out there, but I think there’s a lot of need for it,” she said.

“I don’t think we cater for as many people as there are experiencing these issues.”

According to Kate, warning signs loved ones should not ignore are restrictive eating, isolation, and obsessive weighing.

“Restrictive eating is probably the main one,” she said.

“Are they isolating themselves from their friends? Are they restricting what they eat? Are they weighing themselves every day?”

She also said constant dissatisfaction with body image can be a clue that someone is struggling.

Kate also warned that even well-meaning comments can sometimes land the wrong way.

“One of the least helpful things you can say is, ‘you look great’ or ‘you look well’,” she said.

“That’s generally seen as, ‘they think I’m fat. They think I put on weight.’”

Instead, she believes the most helpful support is reminding someone who they are outside of the illness.

“Encourage the person with the eating disorder to separate themselves,” she said. “Try and bring out that sparkle in them as much as possible. That is like kryptonite to an eating disorder.”

Kate noted recovery has given her “an incredible amount of insight into eating disorder recovery.”

And now, she is using that insight to help others find their way back to themselves.